Kirstin Lamb | Wall and Floor

November 4, 2020 - January 3, 2021

Providence, RI - Periphery Space @ Paper Nautilus is pleased to announce an exhibition curated by Barbara Owen featuring the work of Kirstin Lamb opening in the first week of November.

Lamb describes her new work as a "love letter to the studio."

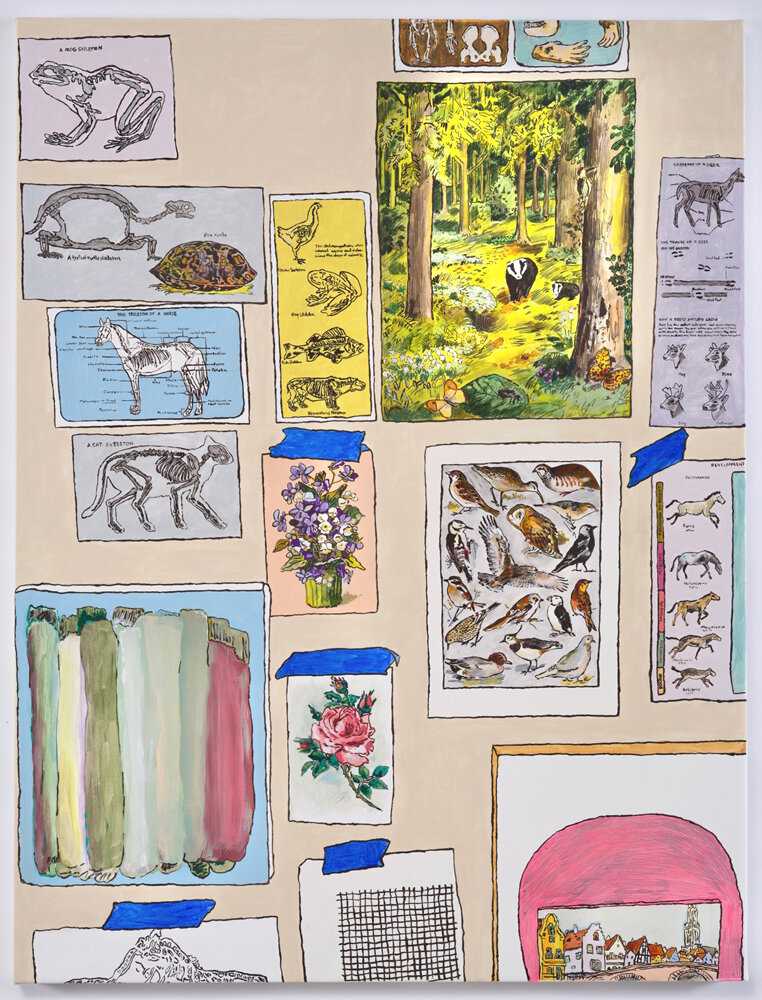

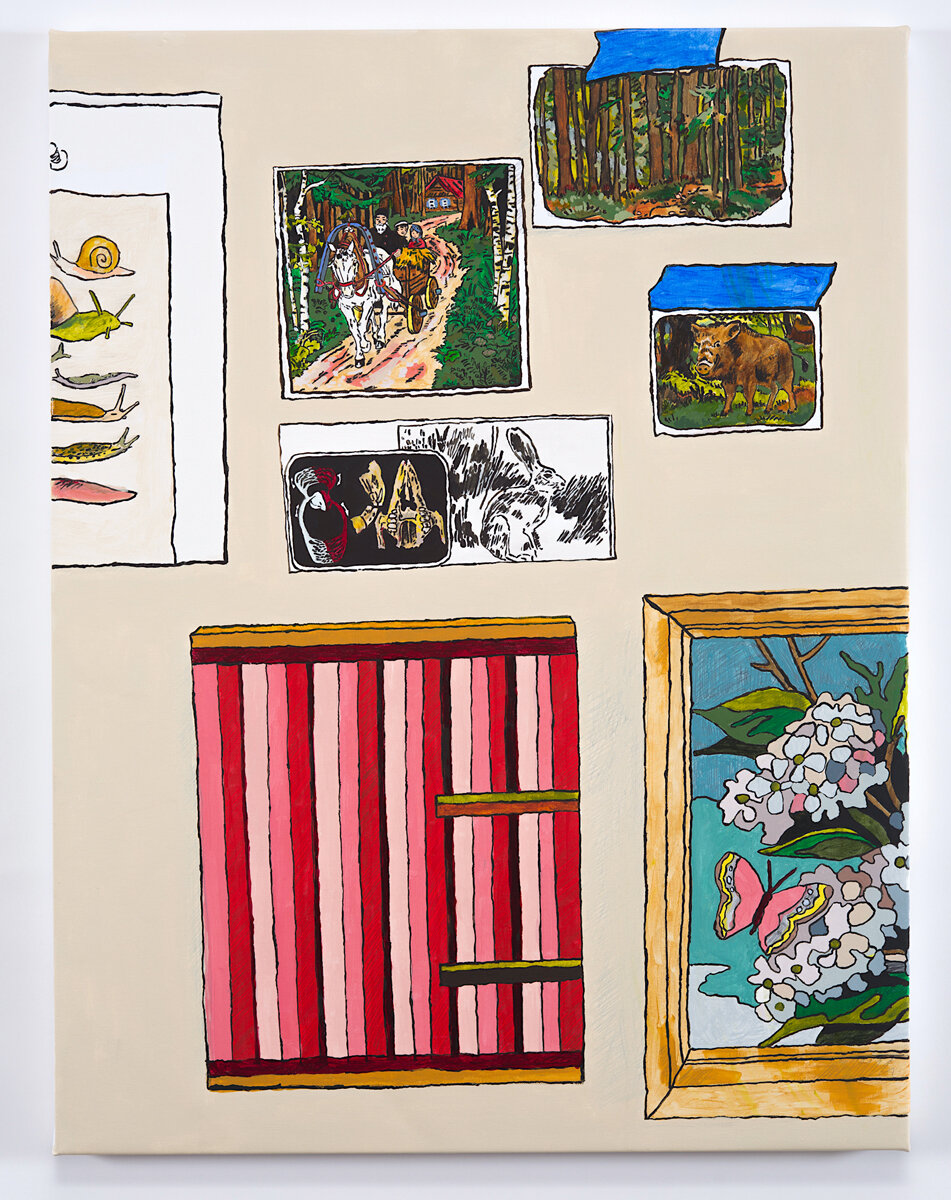

The paintings in this show were made upon a return to the studio after an eight-week separation during Covid lockdown March through May. While she was at home, Kirstin began hanging objects in her home in a way that mirrors her studio's accumulation of papers, images, and books on the wall. She then made linear drawings from these arrangements, including her collection of catalogs, saved postcards, or one of her finished paintings. The final artworks shown here grew out of those initial drawings made in quarantine.

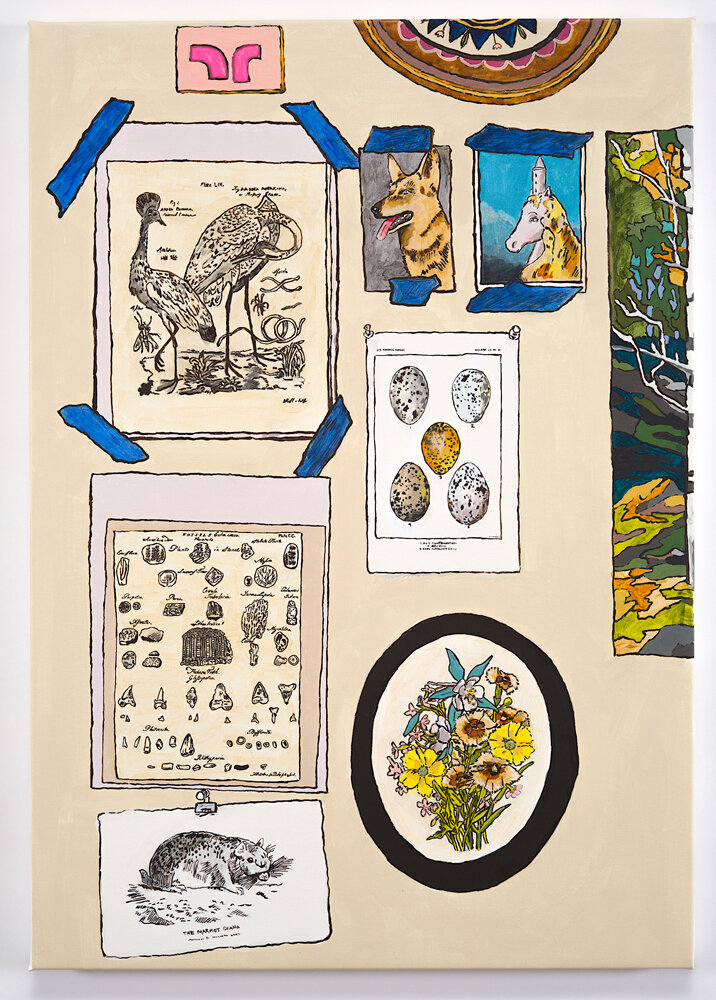

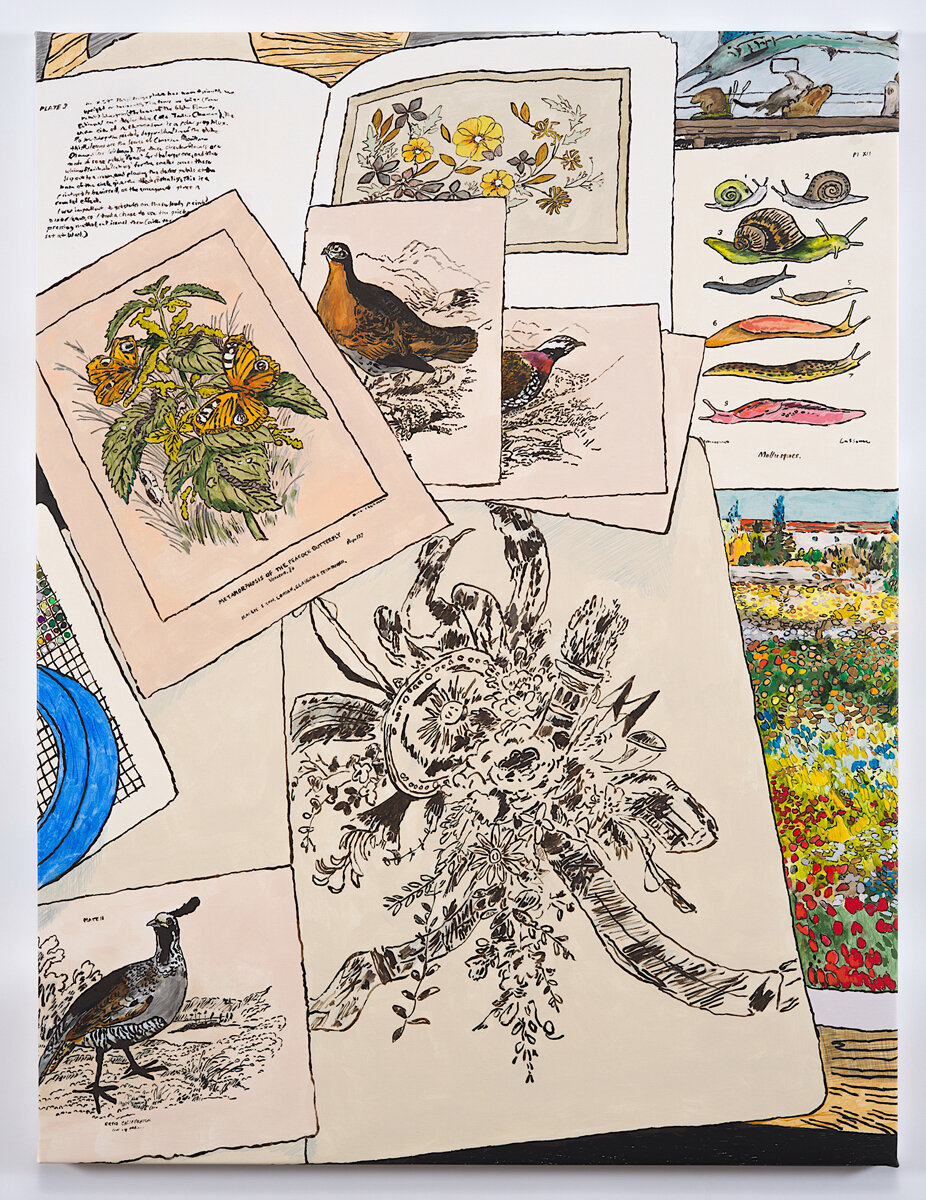

Kirstin creates a still life salon-style using blue tape to temporarily affix and easily arrange images on the wall. In the case of the floor, she layers book illustrations and catalogs open to the page she loves, a print of a landscape by Van Gogh working in Arles, for example, and then stacks it next to a roll of blue tape and a color chart. She considers these to do the "duty of the salon wall without the labor of hanging multiple works." These are charts of influence, love, accumulation, and art-making.

The two large works on canvas and several smaller drawings on canvas are some of the first pieces she created upon her return to her studio - made specifically for this show at Paper Nautilus (Providence, RI.) For Lamb, like other artists in the area, Paper Nautilus is a source of inspiration and material. Aside from books, it has an extensive collection of vintage science, botanical, and natural history illustrations, sorted into categories in wooden drawers -for a few dollars, one can buy these by the page. In Kirstin's studio, they find their way into the still life's she sets up for each piece.

This type of visual design gives a clue into her practice, as she draws from a specific way of working, one that references Trompe-l' œil and the still life of the 1800-1900s. Artists of that genre often depicted the ephemera of every day, including the artist's tools, correspondence, and works in progress, all in one painting. (artists like Jean-François de Le Motte, Trompe l'oeil with Palettes and Miniature, 1635- 1685). In Lamb's take on this genre, she alludes to the artist's role as a collector of images and the illusionistic aspect of the trompe l'oeil. She integrates the objects and display style of her forebears but stops at linear drawing. She does not continue to develop the illusion or falseness of depth; even the color remains flat, unlike in other series, where objects and people are depicted with almost photographically realistic detail. Instead, in this new work (as she writes in her artist statement), she chooses to "cartoon the space, introduce photographic crops that disrupt awkwardly, paint thin layers where there should be thick."

Lamb keeps things flat, straightforward, and truthful despite the intended visual illusion used to trick the eye that Trompe-l' œil seeks to achieve. It's as if she does not want to mislead us or get herself caught up in that deception – at least not now. Kirstin seeks a kind of honesty and straightforwardness in her painting presentation, her intent not to fool the eye but present a kind of chart of the studio, a loving representation of what inspires her in hopes it might inspire someone else. She is "lionizing the project of the artist" in her small way and "sharing her wall so I and others may make in the face of whatever comes next."

_

Biography

Kirstin is a painter living in Providence, Rhode Island and working in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Kirstin studied painting at the Rhode Island School of Design, graduating with an MFA in 2005. Kirstin’s work has been shown in venues across the country and abroad, recently showing in group shows at the Wassaic Project in Amenia, NY, Co-Worker Gallery in Toledo, Ohio, the Fruitlands Museum in Harvard, MA and Providence College Galleries in Providence, RI, among others. She has attended residencies at the Atlantic Center for the Arts, Vermont Studio Center, Bunker Projects, the Wassaic Project, the Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts, The Ora Lerman Trust Soaring Gardens Artist Residency, and the Sam and Adele Golden Foundation. Kirstin received a RISCA fellowship in Painting for the 2020 year, a Rhode Island state arts grant, and has been able to create a new body of work to show with Periphery Space @ Paper Nautilus, an art space in Wayland Square, Providence. Kirstin recently completed a two- year contract curator position at The Yard, Williamsburg, a coworking space in Brooklyn that hosts solo and group shows quarterly and has begun planning online and new curatorial projects in Rhode Island.

______________________

Interview

Shana Dumont Garr interviews Kirstin Lamb on the occasion of her show “Wall and Floor” at Periphery Space @ Paper Nautilus.

Shana Dumont Garr is a writer based in Acton, Massachusetts, and the Curator of Fruitlands Museum, a property of the Trustees, in Harvard, MA.

~

Shana Dumont Garr: Kirstin, this first question will have a bit of a preamble to establish our relationship.

When I was first introduced to your work, I was so intrigued and attracted to it because it seemed to me that you were illustrating the very way I was thinking as I got to know the Fruitlands Museum collection. Focused upon the 19th century, it is literally dated, and the contrasts of placing art next to each other felt like a productive means to gain headway on both understanding it and sharing it with others.

Kirstin Lamb: Shana, I’m so excited you feel that way! I love representing the studio wall as a salon wall and curiosity cabinet. I feel like the way I can understand objects, art-making, and day-to-day human relationships are frequently object-oriented comparison and placement. I feel like I speak more through organizing and re-organizing objects than I do through clear speech. There is something about imaging that relationship, analyzing it, that is helping me figure out what I do. I used to re-arrange the furniture to deal with emotions and fear, so I seem to correlate objects with ideas and feelings. I know many objects have complicated political and historical histories, but the role I frequently inhabit as an artist is to react to them emotionally and formally. I relate so closely to what you do inside the museum and how you tell stories with the objects you care for and display. I feel like I’m trying to just make visible my belief in the studio as a kind of bulwark against pessimism and inaction.

SDG: It takes time to draw, to represent, to render- and I like how you mentioned that in this current series, the drawings are not all about precision. My sense is that for you, drawing and painting is about the process, and about the appreciation of the materials you choose to focus upon. I am curious about the relationship to time in your chosen mediums.

KL: For me, I tend to spend too much time just translating what I’m doing, and I’m trying to just let that be for a while. The obsessiveness of my work can be a trap, but a lovely trap. These new wall and floor pictures are made from drawings that I am blowing up and printing on canvas, so I don’t feel the need to laboriously transfer the original. I feel more freedom to be clumsy with the original, and I feel more freedom to act more simply with the color. Initially, I was interested in obsessive repetition for its effect on my hand, the way it eventually wore down my ability to achieve anything close to facility. But I’ve gotten good at tricking myself into capable repetitive marks, so now, giving myself permission to be free and clumsy is its own reward.

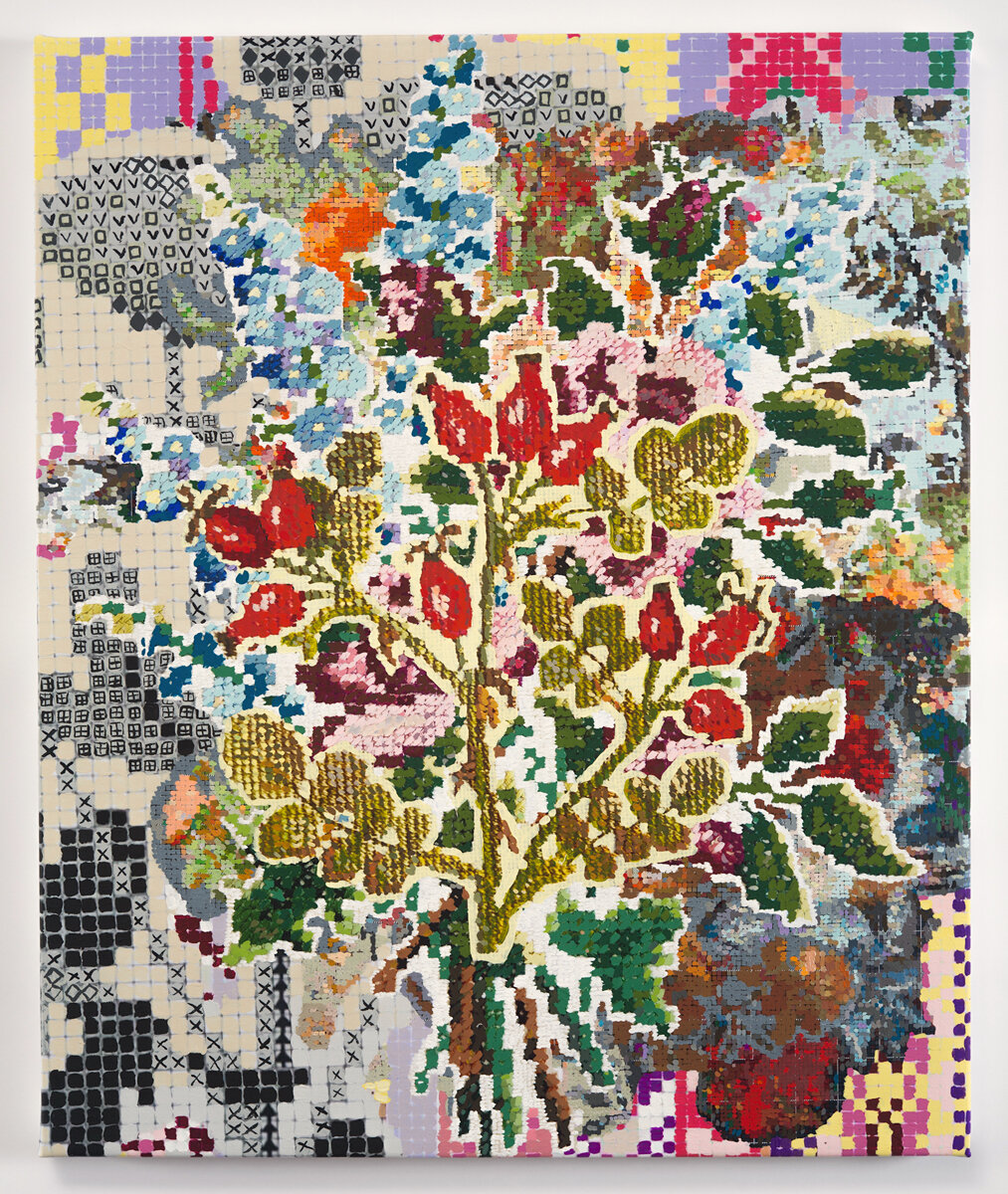

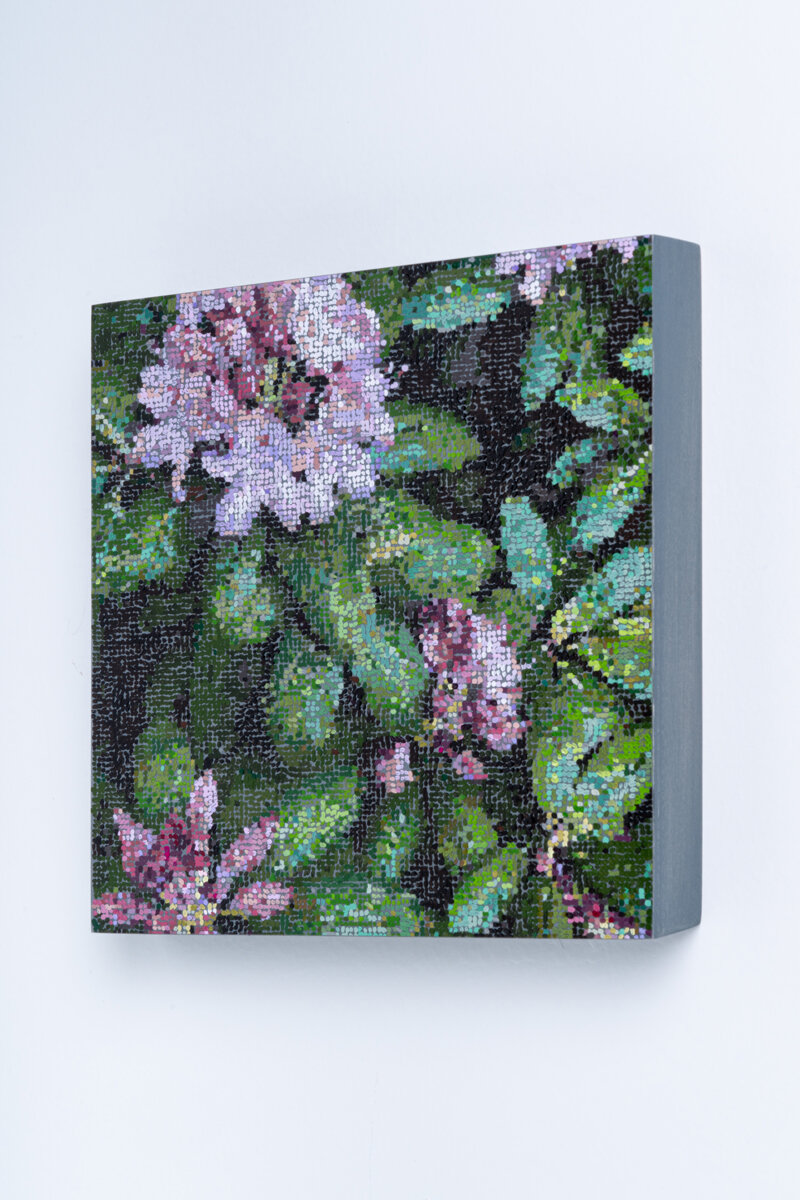

Time for me is part of the meaning of the work, sometimes it is the subject. If I’m not wearing myself down to force my hand to exhaustion, as in my embroidery paintings which involve repeated mark-making in the thousands of marks, I’m trying to do too much to the image to the point of overwhelm. Part of what I actually want to question is what exactly is the value of a work? Is it the time spent with it? Is it the clarity of what it depicts? Does repeating something translate to knowing it better? Does it become less clear? Is that important or redundant? I’m not sure I know the answers, but I lean toward time, labor and accumulation. Those things say something about my identity and the solutions I have gravitated toward, despite modern conveniences and tastes. I want a work that is crowded and awkward, a wobbly salon of particular tastes, overhung and humbly overwrought. I feel I understand things as I examine them and repeat them, and feel that sharing my examinations is my way to share a part of myself. In some ways, my repeated labor is a kind of self-negation just as it is an insistence upon myself and my studio.

SDG: This current series of your paintings focuses more on the natural world than on visual art. However, I’m thinking it is still a blend of images as framed and made by people in many different times and styles. Let’s talk about the relationship between nature and culture, and how styles over time represent changing relationships between people and nature.

KL: Yes, I guess I have moved to looking at images from nature, with a salon-style lens if you will. I’ve been using diagrammatic imagery but trying to place a textbook image of a horse skeleton or a range of fossils into the format of a still life picture.

I’m not sure how I feel about the relationship between nature and culture, as it is related in my work. I haven’t been asked about that before. I feel I’ve been gravitating toward the natural world as we were shut away during the Covid-19 March and April quarantines. When I returned to my studio I immediately began painting the woods as we were not allowed to hike or be on the trails in my state at that time, so I had no access to wild spaces. I could only walk along city trails, and it felt very limiting. There was something about not having access to a space beyond the city that made the world feel so much smaller, so much less alive. I just started work on a large woods painting (stay tuned it will take about a year) and the paintings in this show came along at that time too, first as drawings, and then in their painted form more recently. I guess I was gathering to me what the outside and wild places or even what outdoors and the woods meant to me? My understanding of the woods is an intersection of these scientific diagrams and charts, fairy tale images and images from the Black Forest and the New England woods. These intersect with the daily reality of the art studio (paintings, graphs, tape) to form a kind of synthetic inside/outside that feels sort of true to my emotional state at the time. I hope the pictures show a kind of longing but also maybe a kind of hopefulness, that one can make due and make positive space for oneself and others in the interim.

SDG: Kirstin, in the interest of realism, I am writing again with a new set of questions two weeks after I was able to see this exhibition in person. We met the day after the presidential election when time was seemingly frozen in tense hopefulness. Let’s talk a bit about how this year, from the pandemic to the intense election cycle, has affected your work and/or your artistic practice.

KL: I am trying to make work that fulfills my own needs for color, outdoors, beauty, repetition, and pleasure. Women have historically been shunted into the role of painting flowers or stitching objects to beautify interiors, and now in a moment of stress and fear I feel I wanted to reexamine that, less as a coerced practice and more as something done for joy and expressive pleasure, despite the loss of options for travel and free movement. I wanted to lionize small handwork projects and found textiles. I like the idea of following the patterns someone else followed to beautify her home 30-70 years ago but coming at it like a painter, abstracting and examining the mark, as well as blowing it up to lionize it.

SDG: I love how you articulate bringing time-honored work to a place where process and content are considered in a contemporary manner. Your work was more overtly political in the past-how does your stance on current issues play a role in your current work?

KL: I like the idea that my audience can meet the work where they are. I don’t feel this work is any less political, it is just not aggressively so. I don’t do so much telling in this work, nor do I always explain its purpose. I don’t think the artwork should always lead with its conceptual purpose, though it might have one. I like for folks to unravel why I use French wallpaper, textiles from certain eras, and why I find it helpful to use digital collage and the paintbrush as a stitch. Sometimes content can be playfully arrived at through contemplative visual play as well as through careful political argument. I particularly use French wallpaper patterns from the pre and post-revolutionary moments as a tie in to what they mean politically, but I stop short of eagerly pointing it out. The visuals usually do their own talking and speak of decadence and decor as political actors in their spaces, but also handmades, things that require resources and human labor. I am trying to tie those visuals to a similar visual high period in American culture, the 1950s-70s era home decor, and using patterns from that time feels like an interesting parallel. The labor of my work itself is kind of absurd, everything must be re-touched or re-made with the brush even if it is digital or printed at first blush, and I embrace that as a part of the content. I spend time thinking through what that means for our contemporary moment as makers and cultural producers.

SDG: A more formal question about Studio Wall with Forest, Charts, Skeletons, Florals, and Birds (2020), Is the biscuity taupe an imagined “heaven-place’ or a wall?

KL: The color describes a wall! It is painted with one of my favorite colors, ‘Unbleached titanium.’ It is also the decorator color of my home office, where I am slowly destroying the nice wall with way too many tacks!

SDG: The setting for your exhibition is the exquisite shop, Paper Nautilus. Near your work are drawers of vintage botanical illustrations, and you have talked about this exhibition as a love story to source materials. How often do you come here for inspiration? Where else do you find images that become a part of your work?

KL: I love the idea of a curiosity cabinet and I would say that a shop like Paper Nautilus is the bookseller’s version of a curiosity cabinet. I can acquire some of the objects and take them home to build my own curio, but many of the curio objects in a bookstore such as this are paper objects, easy to transport, not too expensive and easy to maintain. I enjoy building collections of paper ephemera and find that a collection of paper, carefully curated, creates a world, a curated world that I feel compelled to re-present. I try to come when I can, though I couldn’t put a finger on how often, it is when I happen upon the store on a walk in town. I am so grateful Kristen and her store are here every time I do.

Additionally, I do find images I am looking for by searching or happening upon them when reading. Lately I have been looking specifically for Black Forest imagery and images of artist’s studios, so both of those have been searched for and specifically located and printed, bought, or photocopied. Sometimes, images are acquired because they are the kind of taxonomic thing I am drawn to - I prefer a good dictionary of images.

And finally, I do get the many blessed gifts. Friends of all stripes find me with the most wonderful objects and images, and sometimes artwork. Much of it does migrate to the work, slowly, over time. Some things take years to make it into the work, some never do, but I look at them a ton and try to decide what they mean.

SDG: I love the way you combine images from books and your own works in new composites. Let’s talk about the balance between appropriation and, as you have put it, re-presenting. Perhaps you could mention other artists whose work has influenced you in this regard?

KL: I have a love affair with re-presenting the already made, in my own hand. I spoke with a painter friend recently and decided that my version of authorship involved the brush and paint and the tremors and failures of my hand, not the imagery or anything else depicted. I was really interested in how translating something with my hand, however mechanically, could make it mine. This has set me on a course to maniacally repaint everything in my scope, sometimes with my own authorial revisions, sometimes without. But what is always important is my hand doing the painting. I feel I can appropriate when I re-scale and touch a thing myself with paint or drawing. My hand, my personal clumsiness, my personal misfires on color choices, my mistranslation reads to me as a way to allow for the appropriation of other works I would like to talk about.

When I first started making pictures of paintings and artworks, it was a kind of wish to build installations of leaning paintings, which I did fulfill, thankfully. But in the process, I learned about artists in the Dutch high period who were charged with re-imaging the collections of princes and nobles such as David Teniers. His salon portraits of collectors in front of their entire amassed collections fascinated me. Interestingly, he was also responsible for the first catalog raisonne, a printed copy of an entire collection. He drew each artwork and then engraved and printed a book of the collection to be distributed. A revolution for its time. These copies were advertisements of the collector’s wealth and power, but it was also a form of sharing and talking about the collected artworks.

As much as I understand and wish to critique the power structure this implies, I am also interested in the idea of images of images as re-contextualizing and re-structuring the conversation of objects. Objects can be absent still be talked about. This was revolutionary at that time and is now commonplace with the advent of photography. But hand painting or drawing a thing still has a talismanic power to give an art object a certain special aura of value, I would say the value of human labor. So in translating the objects by hand, there is a special value in repeating them and scaling them, transplanting them.

I have also been very interested in many of the artists from the Pictures Generation of the late 70s, early 80s. I find Louise Lawler specifically influential. Her images of artworks in collections as both photographs and line drawings forced me to look at the way in which a Pollock, say, lived with a 18th-century French soup tureen. I find her critique of the art as decor both influential and inspiring. Perhaps, it has made me hew closer to decor and further from overt critique? Is that fair to say? Can decor share the role of critique?

SDG: Your questions and the time period you last referenced also recall for me the realization Jeff Koons gave me, that kitsch had a role in fine art, and vice versa. It made me think of my grandmother’s living room in an entirely new way! I think your work removes boundaries between genres in all the best ways. Could you please elaborate on the visual syntax you create by painting disparate images into one new scene?

KL: If I want to have a visual sentence about Sherrie Levine in dialogue with a story about Rapunzel, it might be helpful to copy a work of hers adjacent to a story illustration? I find these juxtapositions reveal themselves to me over time, I am truly interested in making combinations and asking different things of them. So I combine artist’s studio imagery, with works from art history, with paper ephemera and illustrations and other visual photographs and objects. I like to look at paintings like Rauschenberg’s “Rebus”, to think about visual storytelling as sentence structure. One image follows another, and you tie them together through inference and making poetic visual-verbal connections. A painting is a kind of poetic puzzle, no?

SDG: Would you consider the art-making process like journaling? Does your personal history come across in the work?

KL: I do sometimes consider painting to be tied to my personal history, but I wouldn’t consider each object imaged to have the talismanic symbolism of an object in a still life. So I may image 3 different pictures of animals and cartoons that come from the Black Forest because I am thinking of my German background and family ties to that area, but the particular animal, say a Boar, doesn’t stand in for any particular person or idea, I was just interested to image a boar and put it next to a storybook image. I think the images in context create a narrative, and perhaps a threat, I am interested in the perceived mystery and threat of the storybook woods and find that the accumulated images should suggest that, but each particular image does not stand-in for a particular idea or person in my life. Boars are quite violent, stories have violent passages, especially early fairy stories, and I have been rereading The Uses of Enchantment, Bruno Bettelheim’s book detailing the dark roots of some of our best-known fairy tales and the implications that have in our re-telling. I am interested to understand what imaging these things together does. I know what the images are, a kind of taxonomy of certain woods that has symbolic and personal meaning to me. Though I feel like one brings particular allusions and ideas to each image. These aren’t quite still life paintings and they aren’t quite mood boards, I prefer painting-as-curation, as it allows for each object to have its own identity and bounce off the other objects in the painting. I am imaging my own personal shows, however off-kilter. My own sentences and sometimes poetic thoughts, sometimes not fully realized, just studio curations that get solidified into paint, an organized record of something ephemeral.

SDG: I like how you speak of meaning not always being the first reason for selecting an image. You mentioned painting-as-curation. In addition to a visual artist, you are a curator and a writer. How do these practices interrelate for you?

KL: The paintings have frequently chased what I have written about them in the past, I used to have this very rich idea and word-led practice. Something switched from words to pictures about 5 years ago, my notebooks were filled with lists and paragraphs and suddenly became all pictorial. I found myself imaging lists of potential paintings, in grids. Instead of making a list of words of paintings I wished to make, I had a list of drawn images. These became what I now call “painting as curation.” I was curating from my own list of images, or taking one image and repeating it in another.

I feel like I have created this artificial boundary between maker and curator which sometimes spurs me to create more, and think more clearly. I have found myself interested in the history of museums and curiosity cabinets, still life, and handicraft all through this strange way of writing/curating/making.

I find that when curating I look for art that deals with concepts I’m learning about or dealing with in my own work. I have organized shows that cover the woods, dots and mark-making, flowers, and interiors. I like to have a sense when curating other artists that they are game for reading into and through the work, allowing for multiple reads, playful reads, dark reads. Someone sees a dot painting, someone else sees painful repetition, someone else sees meditative mark-making, and another viewer still sees the privilege to make something without a political purpose. I find the conversation between these interpretations to be the truth of the work, and try to foster conversations through visual juxtaposition, writing and discussion. I enjoy other artists and their generosity on this front, it is such a pleasure to show my peers and mentors.

Studio Wall with Unicorn, Dog, Flowers, Birds, Eggs, Fossils and Marmot, 2020

acrylic on canvas. 33 x 23 in

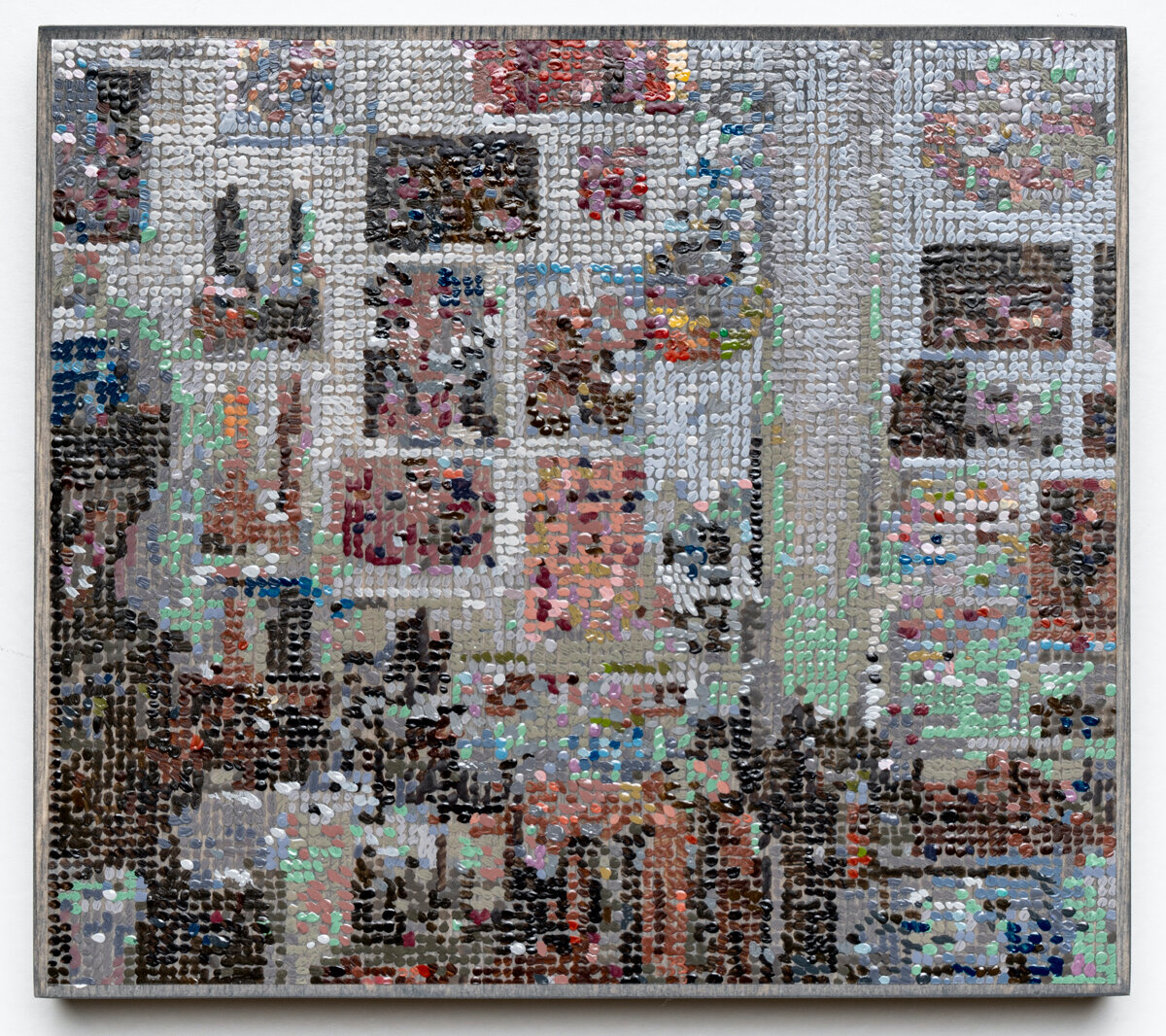

Studio Floor with Butterflies, Snails, Birds, Flowers, Drawing and Van Gogh, 2020

acrylic on canvas, 50 x 38 in.

Studio Wall with Forest, Charts, Skeletons, Florals, and Birds, 2020

acrylic on canvas, 50 x 38 in.

Studio Wall with Unicorn, Dog, Flowers, Birds, Eggs, Fossils and Marmot, 2020

acrylic on canvas, 33 x 23 in.

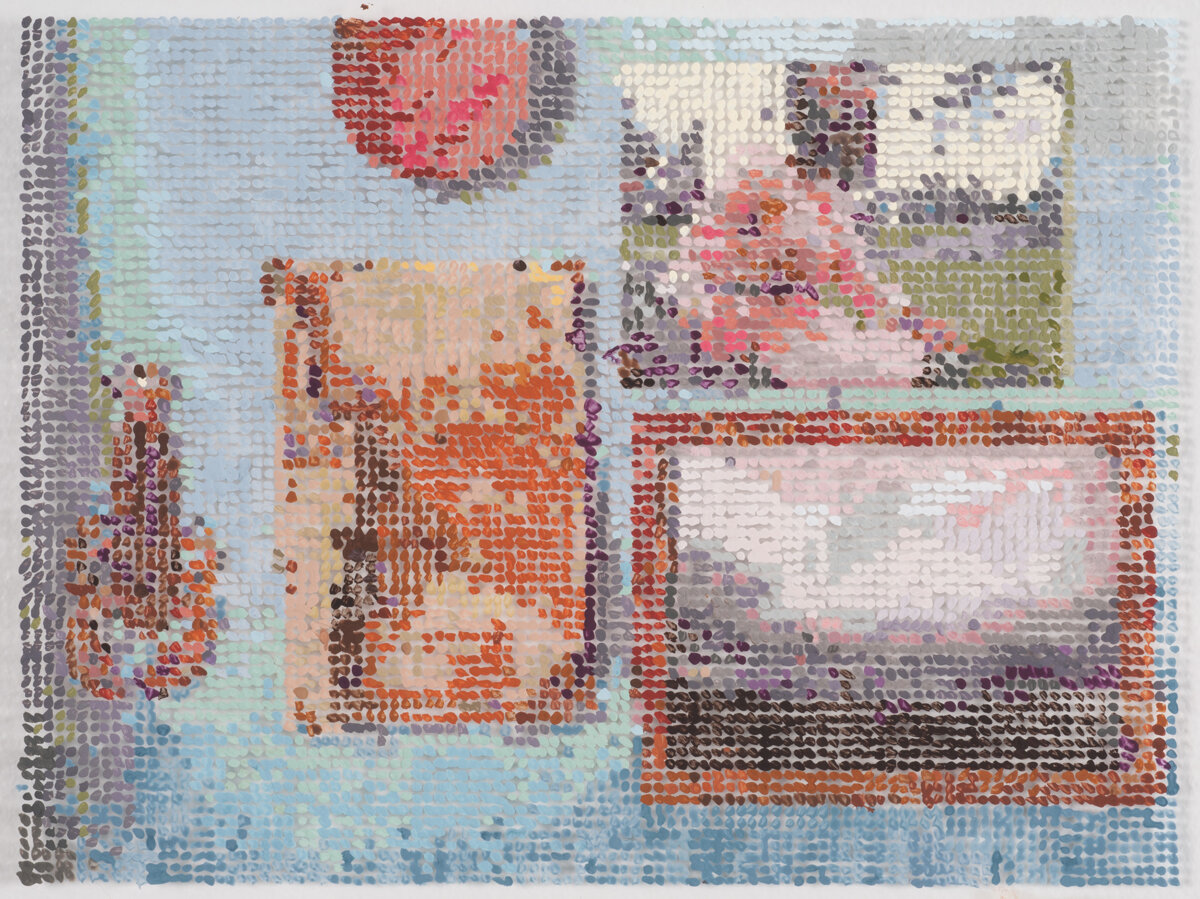

Remix with Rosehip, 2020

acrylic on canvas, 29.5 x 26.5 in.

Remix with Iceland Poppy, 2020

acrylic on canvas, 29.5 x 26.5 in.

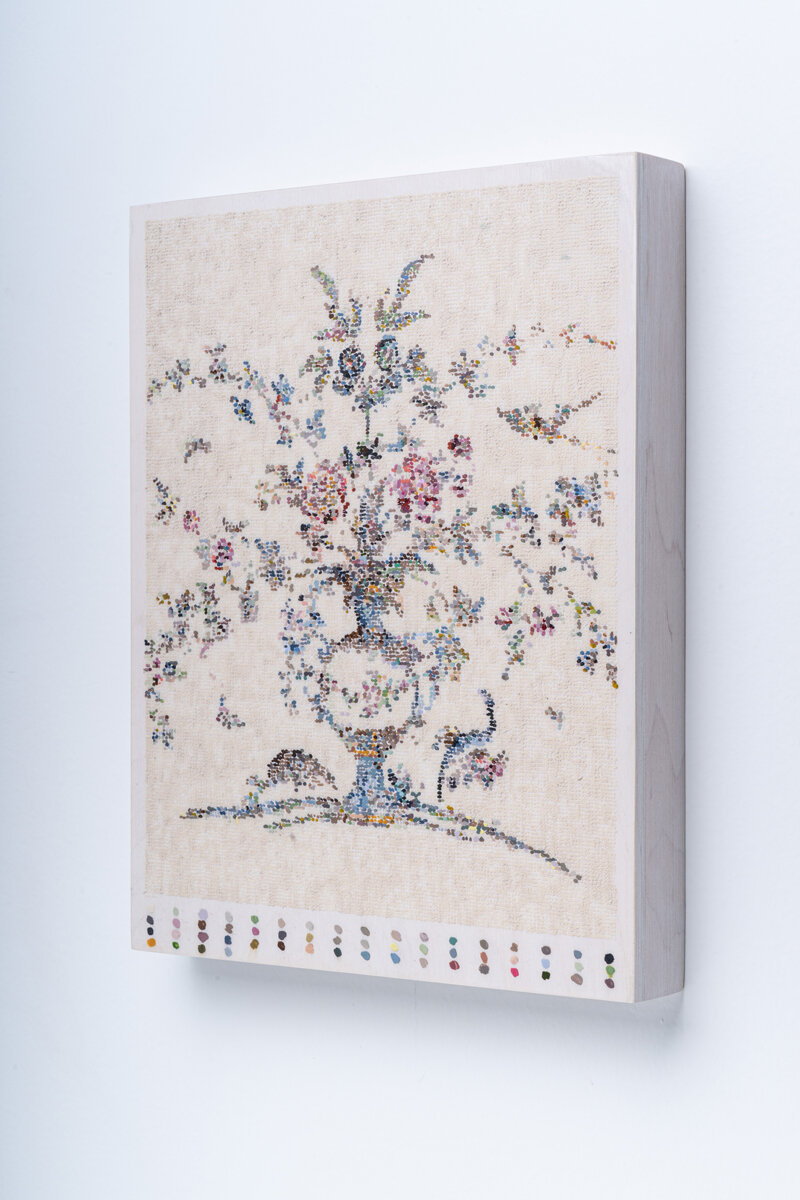

After French Wallpaper ( Scenic Wallpaper Floral Detail), 2020

Acrylic and gouache on duralar on panel, 11 x 8 in.

After French Wallpaper ( Scenic Wallpaper Floral Detail), 2020

side view

Rhododendron II, 2020

Acrylic and gouache on duralar on panel, 8 x 8 in.

Rhododendron II, 2020

side view

After French Wallpaper (Vase with Birds and Palette), 2020

Acrylic and gouache on duralar on panel, 11 x 8.5 in.

After French Wallpaper (Vase with Birds and Palette), 2020

side view

Study for Studio 2006, 2020

Acrylic and gouache on duralar on panel, 7 x 5 in. SOLD

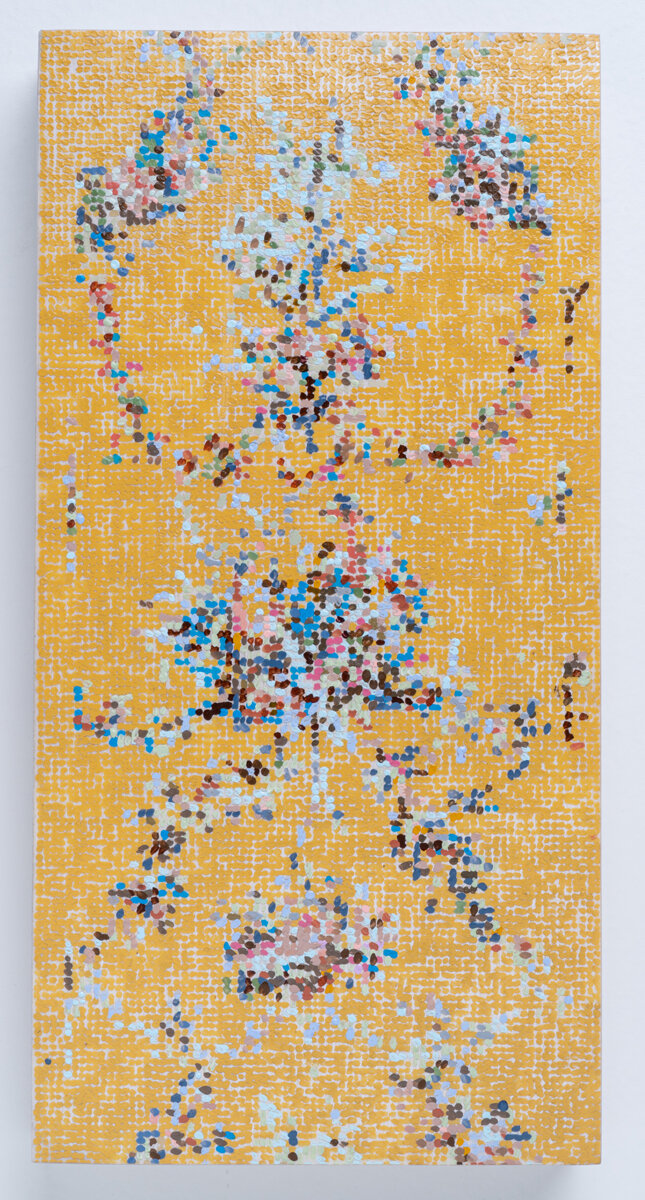

After French Wallpaper Yellow Frieze, 2020

Acrylic and gouache on duralar on panel, 8 x 5 in.

After Tomato Pie, 2017

Gouache and acrylic on duralar on panel, 8 x 10 in.